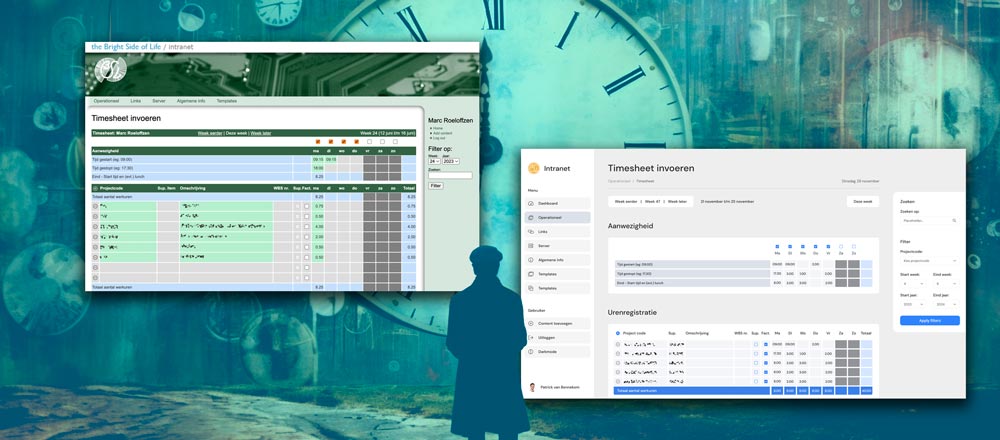

So rounding off our current series of Bright Stories, it’s the turn of Martyn, our director. Martyn created the Bright Side of Life more than 25 years ago, and he’s been developing software since 1977. It’s not easy to condense 43 years of software development into a single blog. In this first part, we find out just why he became a software developer. When he started, PC’s had only recently arrived on the market. Indeed, he personally imported some of the very first IBM PC’s for his employers…

Why software development?

That’s easy to answer. I trained as a Civil Engineer, and after completing my study, I was disappointed. I discovered that Civil engineering naturally favours the construction of safe buildings, bridges, and motorways. They are designed to stand-up for a lifetime, even if some don’t. In the past, innovators such as Brunel were creating a new world, learning on the job. However, in the seventies, you just had to look up the specifications, whatever you were designing. I’m sure there are still innovative projects, but the opportunities are few and far between.

A lucky break for Martyn…

Luckily, Martyn had to develop software for his Masters.

I learnt to program from a book, and believe it or not, my very first program – for which I hand punched Holorith cards, worked first time. This unexpected success hooked me for life. My research allowed me to join a small company set up by a Cambridge University Professor. He and a team of researchers created CRISP® (CRItical State soil mechanics Program), a ground mechanics application for structural soil analysis. My task? To move their Finite Element software, running on Cambridge University mainframes, to something that could run on PC’s.

PC’s were at that time only just arriving in the UK. Many of the companies around Cambridge were creating the very first home computers (companies like Sinclair, Acorn). So although Martyn used PC’s made by Apple (like the Apple II and LISA), and the very first IBM PC’s, they needed major improvements, such as specialised processors, compilers, and D/A converters that could read and control field measurements. Every day was a new challenge. Can you weatherproof an Apple II to work in the Iraqi desert (answer: not very easily 😉 )? It’s these daily challenges that made Martyn a developer. As Jurjen wrote in his blog:

I just enjoy the challenge of solving puzzles to reach the result I want. And the advantage of programming is that you get feedback on your actions almost immediately.

Martyn’s PC CRISP software was used across the world. And believe it or not, versions of CRISP still exist!

Leaving Britain – for good

Hooked on programming, Martyn was less enthusiastic about living in Thatcher’s Britain (which is not very different from Boris Johnson’s Britain).

In 1983 he joined a global CAD/CAM company – Computervision, and later CIS (a company they took over). And that meant traveling – a lot. Systems at that time cost up to one million US$ per workstation . So the clients were either world-famous companies (Boeing, BMW, Pirelli, St. Gobain, Bofors, Ford, Fokker, and Philips), or military. Creating ‘specials’ for these companies, or integrating CAD/CAM into their production system cost peanuts compared to the potential order value.

His Dutch manager suggested he move to Holland, as Schiphol was much easier to use than Heathrow. In 1983 it was much smaller than now (there were no low-cost budget flights). There was a car park where there is now a shopping mall. At the same time, Schiphol (even then) had connections almost everywhere. So his manager’s advice saved him hours on every journey. Although he came over for three months, he’s never lived in England since.

CAD/CAM, a challenging and innovative world

Computervision gave Martyn endless opportunities to learn about different industries, businesses, countries, and cultures.

I had to learn quickly, find a solution to help complete a sale, and then move on to the next challenge. Computervision introduced me to early satellite imaging systems. Creating digital terrain models using stereo-pair images. I had opportunities to work with leading-edge developers from countries such as Israel, and the US, using systems from DEC, Sun (the very first Suns), and (later) Silicon Graphics. I worked (briefly) with some of the people who invented CAD. So I learned something new every day. A truly wonderful time, during which I created astronomical bar bills, and a lifetime of experience that I still apply to BSL projects and technical challenges.

The many challenges associated with working in different locations, with a range of systems, taught Martyn to work under extreme pressure and with strict deadlines. For most of the projects, learning the clients’ business as quickly as possible. Learning what they needed, and if possible, deliver a solution, or propose a solution. This approach is more or less a model for how the Bright Side of Life operates!

Lessons learned

You can break even the most significant problem or development challenge into a series of achievable steps. It’s frequently daunting to look to the top of the mountain (or the end goal of a project). But even Everest begins with the first 100 metres, and then the next. Learning to break things down, sometimes using the project management skills from his Civil Engineering background, helped Martyn immeasurably. Who of you has never been impressed to see how large construction projects like the A2 magically appear, bit by bit. It’s almost as if there is a plan, and indeed there is. Civil Engineering PERT techniques are less fashionable than waterfall/Agile, but there are benefits to all these approaches. If you need a long-term vision, old-school PERT plans can be your saviour.

Another major lesson: reinventing the wheel can be attractive, but can be financially ruinous. Learn to build bridges between systems, or share data between systems. With an incremental approach, significant changes can be made, and at a reasonable cost. Very few companies wish to throw away money. So think in terms of a realistic budget. Then try and find a set of steps that will resolve the most critical goals first. Carry out a cost-benefit analysis to isolate the “nice-to-haves” from the “must-haves,” selecting individual features on their merits. Pluck some of the low hanging fruit on the way, and you will achieve perhaps 90% of your goals, for 20-30% of the cost. Of course, this is the mantra of Agile development processes. However, it’s good to remember that combining off-the-shelf cloud services with a focussed, experienced and well-led team can deliver spectacular results. This is what BSL offers to our clients.

Next time

In the next blog, a little more background about Martyn’s time at ITTWD and Apple. And some more lessons learned.

If you want to contact the BSL team or Martyn, get in touch. In Corona times, it’s not always easy to meet face-to-face for a coffee. However, we’re available online and welcome any opportunity to chat about your next project.